More statistical spree: Sherlock Holmes, the Equalizer

So, after my latest incursion into self-made canonical statistics, here I am again, to vex you with other figures and pie-charts: apologies!

But I thought that there were other data really worth noticing: the number of cases in which canonical Sherlock Holmes takes justice in his hands… to save a culprit or, at least, someone from the risk of undergoing a criminal proceeding (either because he believes the person innocent, or because he thinks they’d get a disproportionately severe sanction).

About the topic of Holmes playing with the law, people tend to mostly notice his INFRACTIONS – that is, the crimes he decides to commit to serve what he believes to be the best interest of his clients, and of justice – such as, for instance, the housebreaking in CHAS, the breaking and entering in BRUC or LADY, and so on. This is, of course, a frequent occurrence enough, as I myself noticed in a previous statistical post, and an interesting fact.

But even more interesting may be the fact that, of all these offences commited by Holmes, a good 38% is (or is akin to) aiding and abetting – which leads us to the topic at hand.Several readers and scholars of the Canon have noticed – and are often attracted to – the ‘superhuman’ aspects of the Sherlock Holmes character – not only his intellectual brilliance, but, for instance, his incredible (for such a slender, even skinny, man) strenght (he bends an iron pocket with his bare hands in SPEC), or his cat-like ability to see into darkness (CHAS). Umberto Eco even compares him to the Count of Montecristo, with whom Holmes certainly shares the great ability at disguising himself, and – according to Eco – the attitude for taking justice into his hands, to achieve what law and tribunals could not.

But here, I think, we find the great difference, not only between these two fictional characters, but between Holmes and many other epigones of his, both in detective stories and amongst other fictional popular characters: Holmes is NOT an avenger, on the whole.

Yes, he shares the idea that crimes must be punished, that culprits must ‘pay’ for their deeds; he is a child of his age and have no objections, for instance, to death penalty, nor to the mainly retributivist ideology which characterized the Victorian criminal system (and still affects the majority of contemporary criminal systems).

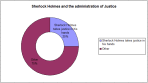

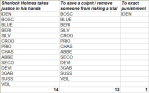

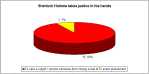

And yet, he is more human, and more modern, under many respects, than that system, than his society: he is capable, for instance, of letting a confessed – and quite vile – criminal go, in BLUE, because he is aware that “sending him to jail would make him a jail-bird for life”, and this is not what he thinks would be justice’s and society’s best interest.And if it’s true that Holmes appoints himself judge and jury in a good 25% of canonical stories, it’s also true that only once – in IDEN – he does so to personally inflict punishment on a culprit he knows the law could hardly reach. But even in that case, all he does is to threaten, to scare the rascal: he actually DOES NOT exact proper punishment.

(And, no, other cases, such as CHAS, don’t qualify, either: here Holmes break the law a first time in order to rob Milverton, not to punish him, but to save his client’s reputation; and when he DOES actually take justice in his hands, it is to ‘acquit’ and save from the police the woman who killed the blackmailer.)

All the other times – 13 cases on a total of 14, the 93% of times – the self-appointed judge and jury Sherlock Holmes takes justice in his hands in order to save a culprit or, at least, to remove somone from risking a criminal proceeding whose outcome could be uncertain and, in case, disproportionate (such as with Mr. Croker in ABBE, for instance). Sometimes Holmes does so in order to avoid a scandal which would involve also innocent people (in PRIO, for instance, we may imagine that he considered also the situation of the little Lord Saltire, an innocent child who would have suffered from the scandal, had his father’s role been publicly revealed by Holmes); some other times, because he thinks the punishment, as provided by the law and/or foreseeable after a trial, disproportionately severe; and other factors, too, influence Holmes’ decisions, such as human compassion and empathy, the consideration of the sufferings already endured by the culprit, and/or of the useful work he could still perform (and by which he could better atone than by rotting in a prison cell: see DEVI, for instance), the idea that some human facts and sentiments could never be fairly weighted out in a tribunal – and so on.

Thus, all things considered, Sherlock Holmes, ‘father’ of so many following detectives and ‘equalizers’ of all sorts, stands up as a mostly ATYPICAL literary figure: not so much a righteous avenger, as, instead, mainly – and chivalrously – a protector of the weakest ones, be them victims OR culprits.

And this, I think, is another facet of him being the champion of the light of reason against the darkness of ignorance and prejudice, and one of the things that make Sherlock Holmes an everlasting lovable and beloved character, and a model as well.

This is bloody fierce.

- Comment

- Reblog

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.